What joy: a train lover writing for train lovers

Settling down with a Paul Theroux train book is like a long rail journey with a well-loved friend. You know what you’re in for, and it’s a treat in store. Theroux is great at evoking landscapes and people, and his own love for trains shines through.

One of the gifts he offers to fellow train lovers is explaining why we feel this love, articulating and justifying it. Here’s an example:

“The feeling I had on the Khyber Mail was slight disappointment that the trip would be so short – only twelve hours to Lahore… The sleeping car is the most painless form of travel… Robert Louis Stevenson writes,

Herein, I think, is the chief attraction of railway travel. The speed is so easy, and the train disturbs so little the scenes through which it takes us, that our heart becomes full of the placidity and stillness of the countryside; and while the body is being borne forward in the flying chain of carriages, the thoughts alight, as the humour moves them, at unfrequented stations.

I find this splendid, but it gets even better in the next paragraph, as Theroux continues: “The romance associated with the sleeping car derives from its extreme privacy, combining the best features of a cupboard with forward movement.”

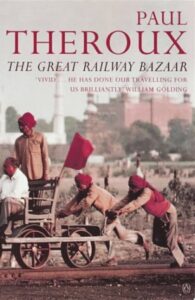

The book is a bazaar in the best sense: a vivid sequence of episodes, as we travel right across Europe and Asia, from London to Tokyo, and back through Russia.

I’ve long believed that a country’s character is embodied in its trains, and this book supports my view. Like Theroux, I prefer the sociable trains of India and Pakistan, whose leisurely speed means you can sit in an open carriage door and enjoy the scenery, to the antiseptic bullet trains of Japan, where you’re sealed in, and the landscapes go by in a blur.

Some of the most striking episodes of the book are in South Vietnam. He’s there at a poignant time, after the Americans have pulled out, and before the North clinches victory. The railway along the coast was often attacked by the Viet Cong, but Theroux bravely travels the three segments still operating. He comments:

“From the cruel interruptions of war, they had stubbornly salvaged a routine: school, market, factory. At least once a month the train was ambushed. But these passengers made their daily trip.”

He also comments on the outstanding beauty of the landscapes and coast, something rarely mentioned about Vietnam by anyone. “Of all the places the railway had taken me since London, this was the loveliest.”

The most elegant train shows up in an unexpected location:

“Here, on the Vostok, parked on a platform in what seemed the most godforsaken town in the Far East, was a compartment that could only be described as ‘High Victorian… I had an easy chair on which antimacassars had been neatly pinned, a thick rug on the floor… my pillow was full of warm goose feathers.” Sadly, the Vostok was only a one-night prelude to the Trans-Siberian, where the train, the landscapes and the people were all dismal.

In these times when exotic foreign travel is near-impossible, this is about as good as it gets for the armchair train lover.