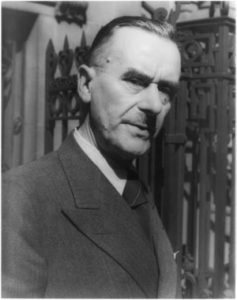

Thomas Mann is an author who deserves to be taken seriously. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 and is one of Germany’s greatest twentieth-century writers. You may know him through the beautiful film of his novel, Death in Venice.

Thomas Mann is an author who deserves to be taken seriously. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 and is one of Germany’s greatest twentieth-century writers. You may know him through the beautiful film of his novel, Death in Venice.

However, The Magic Mountain is not an easy read. It’s over 700 pages long, and not a lot happens. You feel that Mann is forcing his readers to work out meanings, and find their own motivation to keep reading.

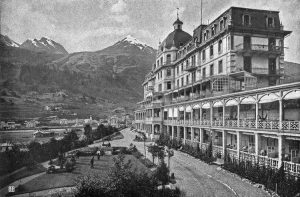

The whole novel is set in a Swiss sanatorium, in the years leading up to 1914. The central figure is more anti-hero than hero: Hans Castorp is a young man from Hamburg who visits for three weeks, but stays for seven years.

The sanatorium is a weird, self-absorbed world, with strange patients from all over Europe. They are preoccupied with their own gossip, flirtations, and novelties. Slowly we realise that Mann sees all this as typifying the state of Europe before the Great War – he writes of “something uncanny about the world and life,…as if a demon had seized power…The demon’s name was Stupor.”

The sanatorium is a weird, self-absorbed world, with strange patients from all over Europe. They are preoccupied with their own gossip, flirtations, and novelties. Slowly we realise that Mann sees all this as typifying the state of Europe before the Great War – he writes of “something uncanny about the world and life,…as if a demon had seized power…The demon’s name was Stupor.”

Another big theme in the book is time. The book itself plays with time: the first three weeks of the story take many chapters, while later, a year can pass in a page. Mann explores different ways we experience time, and aims for us to experience them through the book. For example, he describes waiting as like gluttony, “because it devours quantities of time.”

The Magic Mountain’s complexity lies not in its storyline, but in the layers of allusion and allegory beneath the somewhat bland surface of the plot. These layers are hard for a contemporary UK reader to access. Some characters are modelled on Mann’s 1920’s German contemporaries. And his ideas draw on many other German sources, such as Heidegger and Goethe.

The Magic Mountain’s complexity lies not in its storyline, but in the layers of allusion and allegory beneath the somewhat bland surface of the plot. These layers are hard for a contemporary UK reader to access. Some characters are modelled on Mann’s 1920’s German contemporaries. And his ideas draw on many other German sources, such as Heidegger and Goethe.

The image of The Magic Mountain itself is another example: it has echoes of a German archetype, the Venus Mountain, also found in Wagner: a “hellish paradise,” a peak of abandon where all sense of time is lost.

The layers and allusions go on and on: Greek myth and archetypes are another source. It’s a deep, intelligent book, but it demands a lot form its reader.